ST. LOUIS — Byers' Beat is a weekly column written by the I-Team's Christine Byers, who has covered public safety in St. Louis for 15 years. It is intended to offer context and analysis to the week's biggest crime stories and public safety issues.

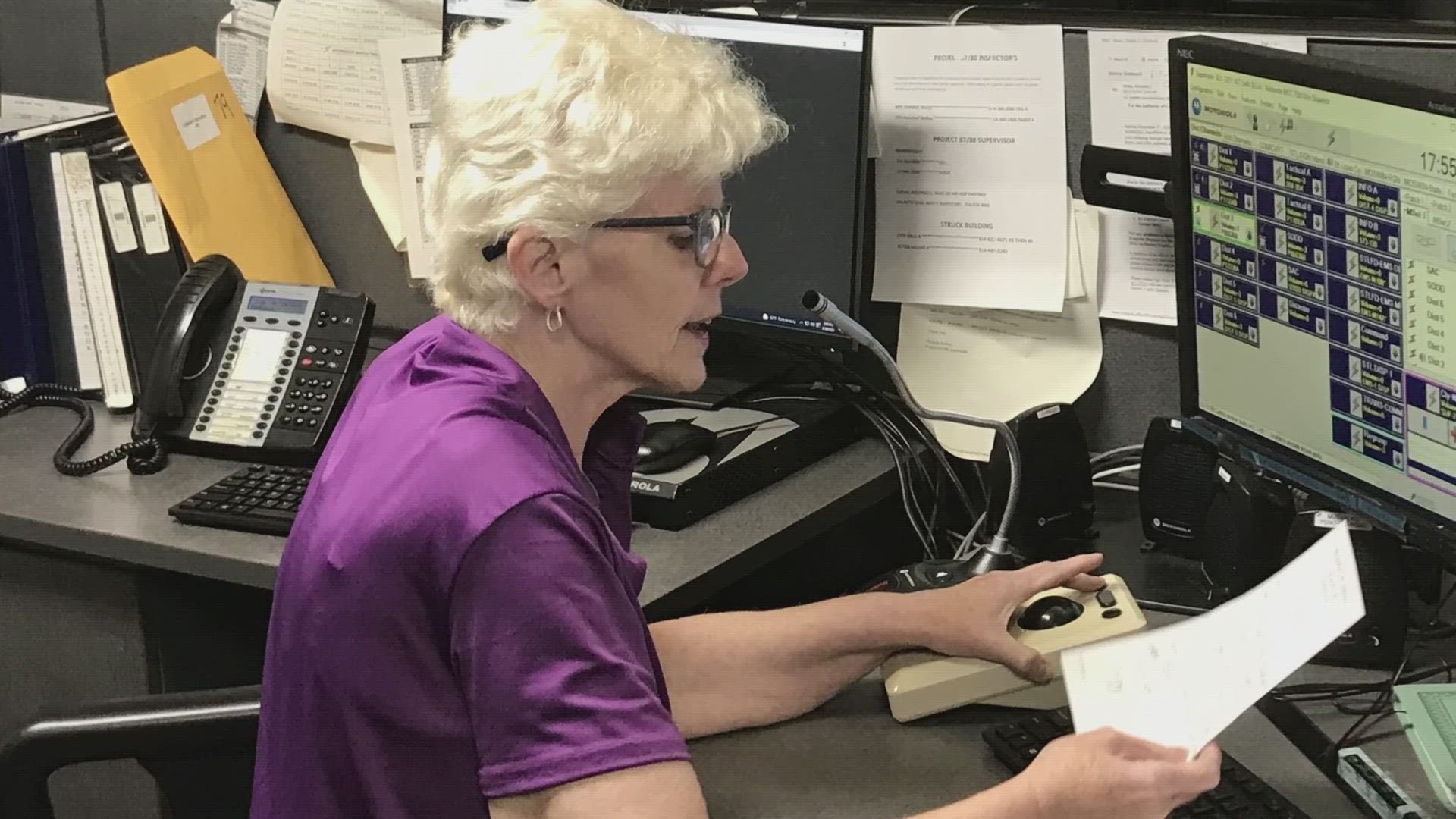

Maureen Ramsey says she walked away from the city’s 911 dispatching center two years ago after a 44-year career there because the environment had become too toxic and the workload too untenable.

Now, when the system is arguably at its worst, with viewers contacting me nearly every week with a new horror story about how the city’s dispatcher shortage made their emergency situations worse, Ramsey says she wants to go back.

“I would go back in a heartbeat because I have a passion for that job, but I don’t think they’d have me back,” she said, adding that she has done several media interviews criticizing city leaders for letting the situation get this way. “I told them two years ago, people were going to die because of this.”

Now, there’s at least one lawsuit filed this year by a grieving family alleging just that.

Ramsey also says the city’s dispatching crisis has been a long time coming – and dates through at least two previous mayoral administrations.

In 2013, the city got control of its police department after the state ran it for most of its 150-plus-year history.

Mayor Francis Slay fought for most of his 16 years in office to get local control of the department.

When it finally happened, Ramsey said the department – including its civilian dispatcher employees – all fell under the city’s Personnel Division.

And Ramsey says, standards changed.

“We’ve interviewed people who are wanted,” she recalled.

Lists of job candidates were also a year old or more – so by the time Ramsey said the city would call potential candidates, many had found other jobs.

“There was never any urgency to fill the spots,” Ramsey said. “We were just kind of thrown to the wind.”

Then, in 2017, during Mayor Lyda Krewson’s administration, voters in St. Louis approved Prop P to raise salaries for first responders.

Police officers got about a $6,000 raise – but the personnel division did not extend it to civilian employees, Ramsey recalled.

“It was like a slap in the face for all civilians,” she said.

Now, Ramsey says, the problem is a crisis.

Nearly every weekend, police sources send me internal memos showing dispatchers are assigned to manage multiple police districts at a time -- a technique known as patching.

In November 2022, 5 On Your Side's Sarah Machi reported there were at one point only two dispatchers covering all six of the city's dispatching districts.

Mayor Tishaura Jones took office in 2021, and just months after doing so, she pledged to tackle the issue.

Her former Public Safety Director Dan Isom said part of the plan was to combine all dispatchers – police, fire and EMS dispatchers – under one roof within three months.

That still hasn’t happened.

Police and EMS dispatchers are now operating out of the police dispatch center.

Fire dispatchers are still at the fire department’s headquarters.

An automated system now answers calls, giving people prompts to push depending on whether they need, police, fire or EMS services to try to get those calls connected quicker.

Viewers have told me following instructions from a recording is a lot to expect from someone in a panic.

Some say when they get a fire and EMS dispatcher to answer, they are told to call back because they selected the wrong emergency service.

Fire and EMS workers will not respond to scenes without police securing them first.

That's why Ramsey and her fellow front-line police dispatchers answer all 911 calls first and determine whether to farm them out to EMS or fire services.

The Jones administration has also created a new dispatcher category known as Public Safety Dispatcher, which is a dispatcher city leaders say will be trained on how to answer all types of calls.

The minimum salary for the new cross-trained category of dispatcher is $50,000 – that’s $3,000 more than the minimum salary for an EMS dispatcher, and requires the knowledge and skills to do more work than an EMS dispatcher.

Pay raises did take effect July 1 – bringing sizeable raises to some categories of dispatchers.

EMS dispatchers saw the biggest minimum salary jump to $47,000 from $32,000.

But starting pay for police dispatcher trainees – which has the highest number of vacancies and where all 911 calls begin – only went up by $2,000.

It now sits at $41,000.

Ramsey agrees with Fire Chief Dennis Jenkerson, who told me this week combining all three categories of dispatchers under one roof won’t work if they’re not all paid the same.

His department began paying its dispatchers the same as it pays its firefighters back in the 1970s.

That means an entry-level dispatcher makes what an entry-level firefighter does. And a supervisor makes what a captain does.

After those July 1 raises, the minimum salary for a fire department dispatcher is about $53,000 and the minimum for a senior fire equipment dispatcher is $82,000.

After 44 years of dedicated service, Ramsey said she walked out making a salary barely above $60,000.

And she says she’s still willing to come back – but there just aren't many Maureen Ramseys out there these days.